Antarctica is a continent of ice.

From the tallest summits to the deepest valleys, Antarctica is moved, shaped and defined by the ice that envelops it.

INCREDIBLE ICE

Antarctic ice is many things . . .

Habitat

Sheltered habitats under the ice support vibrant ecosystems.

Refuge

At sea, ice provides vital refuge from marine predators.

Respite

Ice floes provide resting places for seals and penguins.

Breeding

Ice provides a platform for breeding and raising young.

Antarctic ice also plays a critical role in regulating the Earth’s climate.

It reflects the sun’s heat, provides a habitat for microscopic plants that absorb carbon, controls global sea levels and generates cold, salty water that helps drive global ocean currents.

LAND ICE OR SEA ICE?

Antarctic ice comes in many forms.

To understand Antarctic ice, the vital role it plays in the global climate, how it is changing, and why it matters, we first need to understand the different kinds of ice in Antarctica.

Land ice (also known as meteoric ice) falls as snow, and forms when snow is buried and compressed by layers of snow above. Antarctic meteoric ice includes the Antarctic Ice Sheet and its ice shelves. Some of the ice in Antarctica is thousands of years old and hundreds of feet thick.

Sea ice is made of frozen ocean. It forms when the ocean itself freezes over. Unlike land ice, sea ice is generally only a few feet thick. Antarctic sea ice is seasonal, forming each winter and melting almost completely each summer.

ANTARCTIC ICE

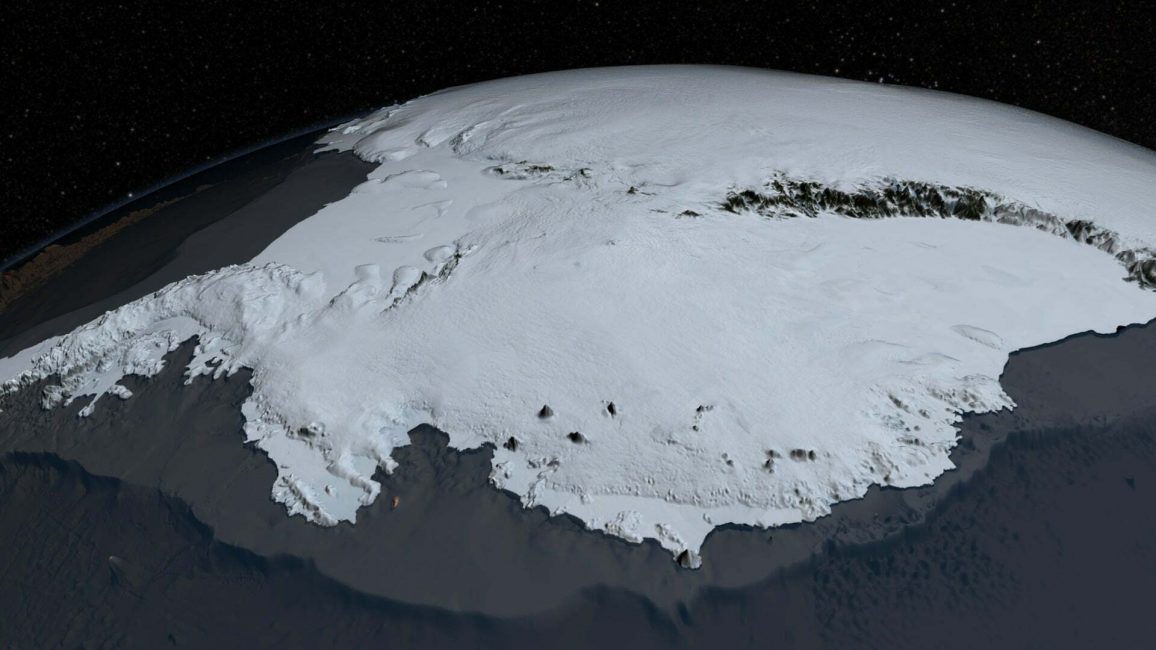

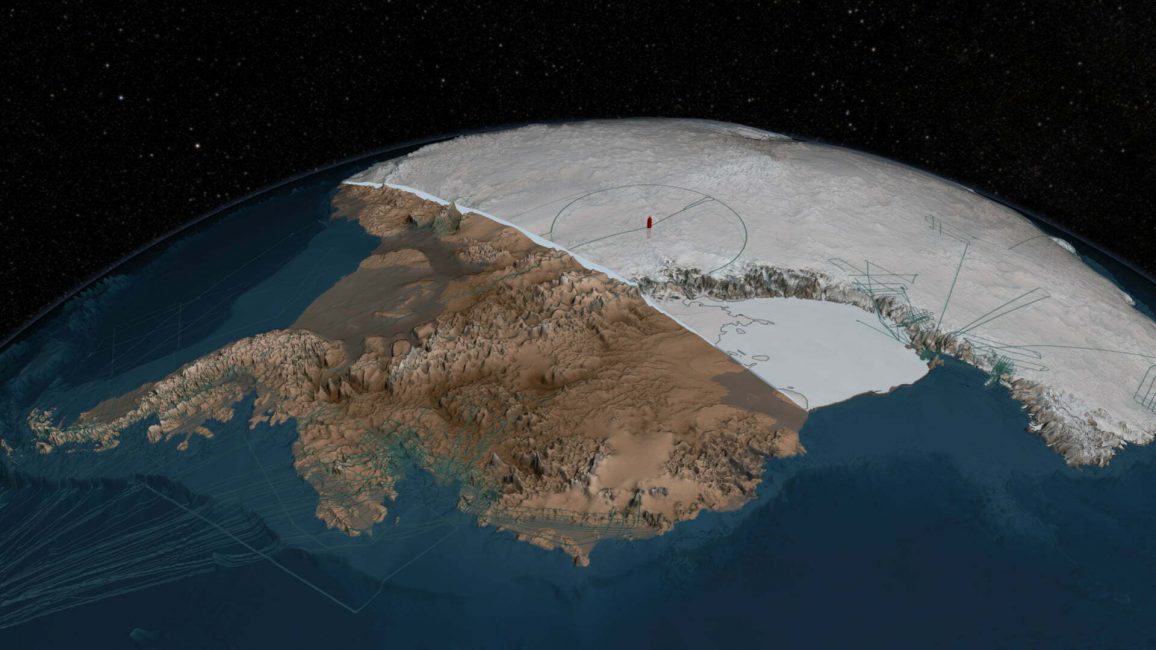

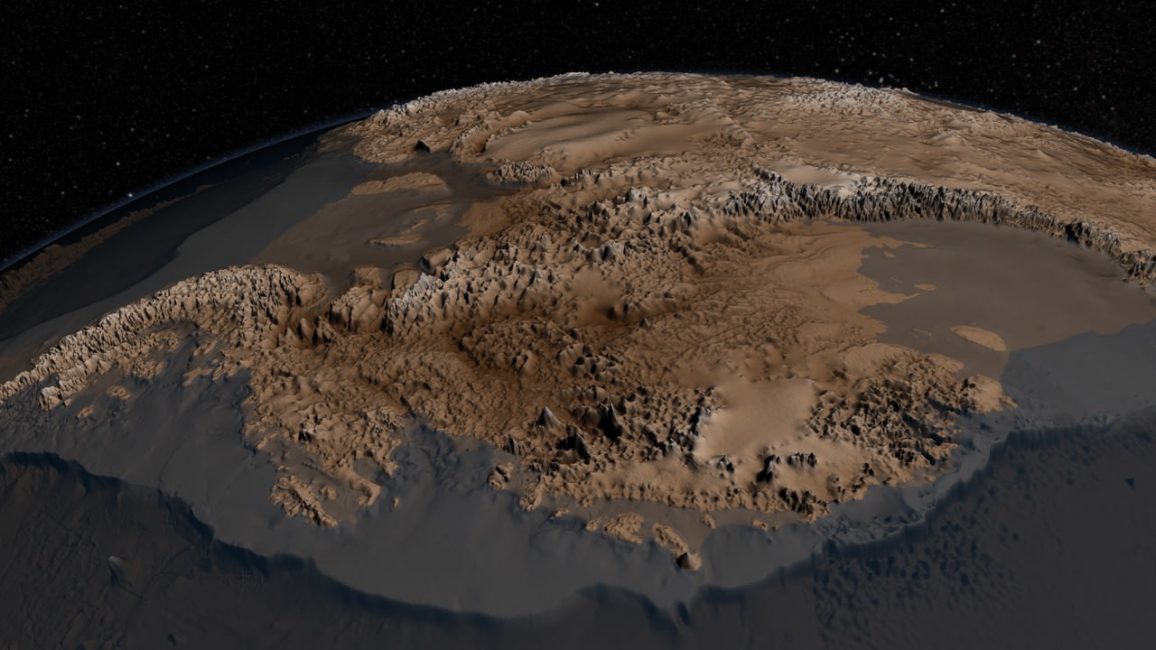

Land Ice: The Antarctic Ice Sheet

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is the largest mass of ice on the planet. It is much larger than the United States, almost twice the size of Australia and about fifty times the size of the UK. If you spread the Antarctic Ice Sheet across the United States and Mexico, they would be covered in a layer of ice around 7000 feet (over 2000 meters) thick.

How did the ice sheet form?

Antarctic Ice

The Antarctic Ice Sheet began as a series of small glaciers, much like the ones we see in high alpine regions today. It started to form between 34 and 35 million years ago. At that time, South America and Tasmania, which had been connected to the Antarctica landmass for millions of years, started drifting to the north. The Southern Ocean began to flow around Antarctica like a great oceanic moat. Global temperatures fell and Antarctica was plunged into what some describe as a ‘34 million year winter’.

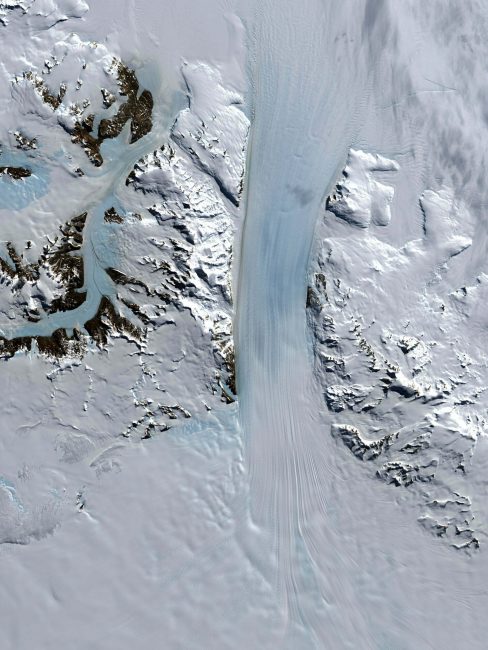

Does Antarctic land ice move?

Antarctic Ice

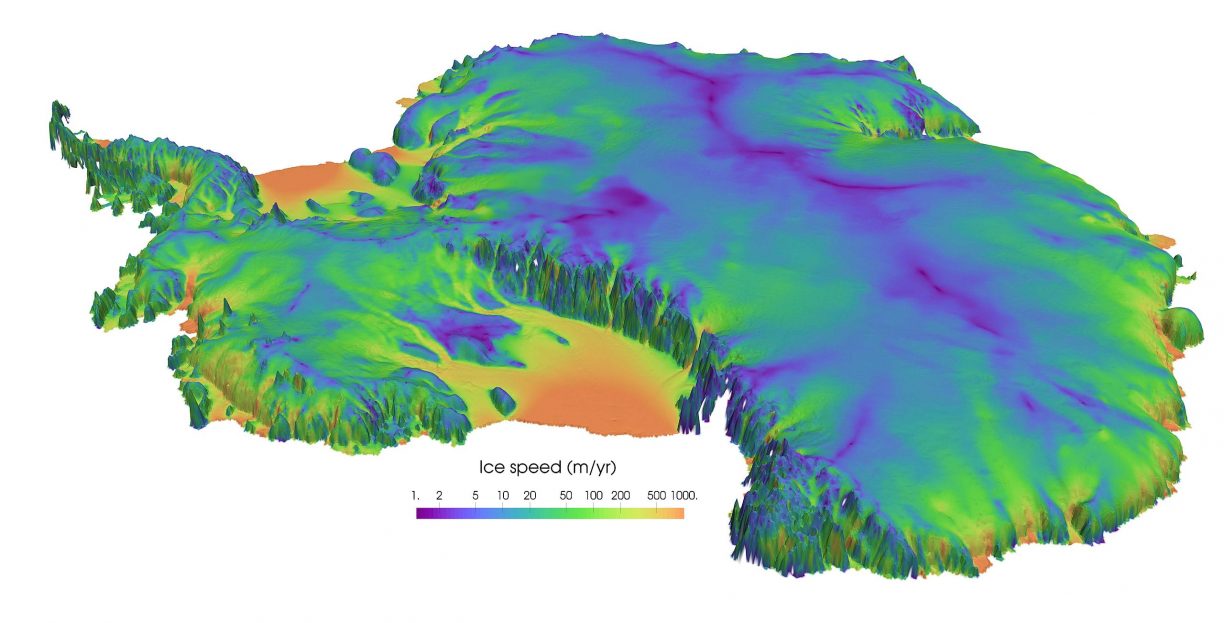

Antarctic ice is always in motion. Powered by the force of gravity and its own colossal weight, it oozes like a slow-motion river from the mountains towards the sea. The ice is also shaped by the constant motion of the wind, which carves it into solid, wave-like shapes and whimsical sculptures called sastrugi.

Exactly how fast the ice moves is influenced by many factors including the steepness of the terrain and the material it flows over. In the middle of the ice sheet the ice moves very slowly, just a few feet per year. In some places, as the ice streams into deep gorges and steep valleys near the coast, it reaches speeds of more than 3000 feet (more than 1 kilometer) per year. The speed of the ice is also influenced by the material it is flowing over. Ice moves relatively slowly over rough, highly textured surfaces like rocks and ridges and speeds up over slippery, soft surfaces like water and sand.

Antarctica’s three ice sheets

Antarctic Ice

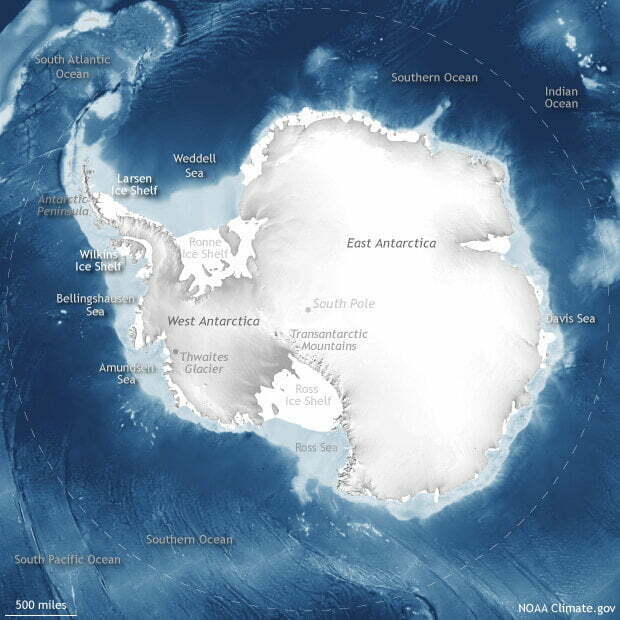

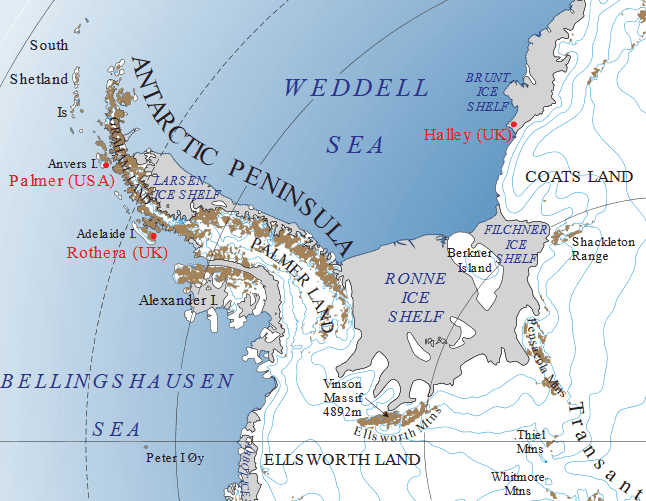

Antarctica and its ice sheet are often divided into three main sectors: the East Antarctic, West Antarctic, and the much smaller Antarctic Peninsula ice sheet.

East and west are separated by the Transantarctic Mountains, which rise about 2.5 miles (4km) above sea level and extend more than 2,000 miles (3200km) along the Antarctic continent.

The Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet blankets a narrow, rocky mountain range, which extends out from the main bulk of Antarctica like a finger pointing towards South America.

East Antarctic Ice Sheet

Antarctic Ice

East Antarctica is the highest, driest, windiest and coldest place on earth. It is also home to the largest ice sheet on the planet.

West Antarctic Ice Sheet

Antarctic Ice

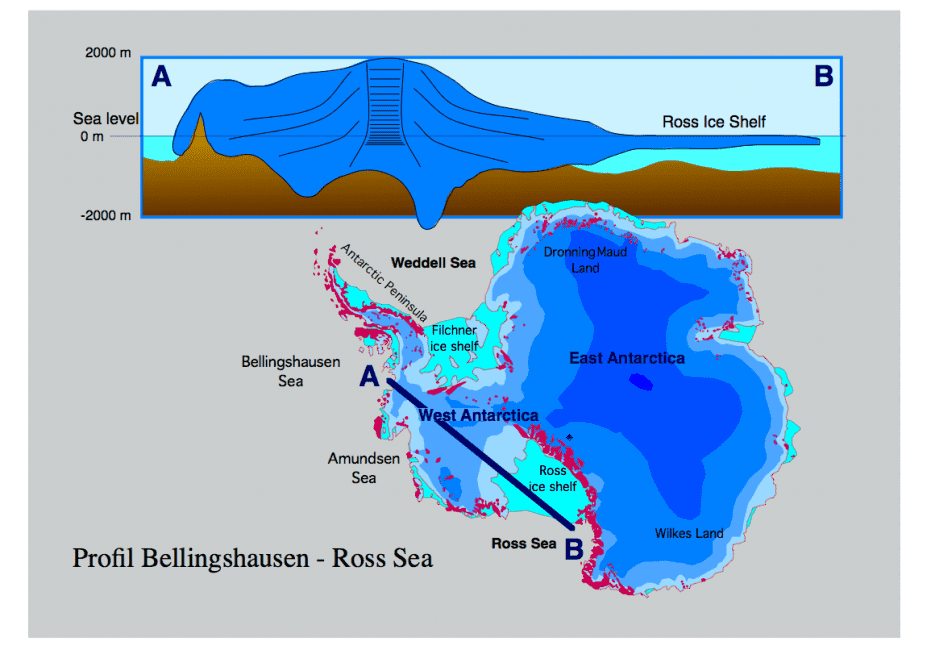

Roughly one tenth of Antarctica’s ice is in the west. Flowing down from the Transantarctic Mountains, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet drains into the Bellingshausen, Weddell, Amundsen and Ross seas via a network of glaciers, ice streams and ice shelves. It holds enough ice to raise sea levels by 10 feet (3 meters) if it all melted.

Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet

Antarctic Ice

The Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet is the smallest ice sheet in Antarctica. Extending to a latitude of 63°S, roughly 600 miles (1000 kilometers) from South America, it covers the northernmost part of Antarctica.

Why is the ice sheet important?

The Antarctic Ice Sheet plays a critical role in the Earth’s climate.

Reflecting

The bright, white surface of the ice reflects up to 90% of the solar radiation that reaches it, helping to keep the planet cool.

Read more

Reflecting

The bright, white surface of the ice reflects up to 90% of the solar radiation that reaches it, helping to keep the planet cool.

Ice has a higher ‘albedo’ (reflective capacity) than the ocean and land surfaces. Dark-colored surfaces like the ocean and land tend to absorb the sun’s energy, lighter-colored surfaces like ice reflect it back out into space. Together, they regulate the overall balance of heat energy on the planet.

As the largest ice mass on the planet, the Antarctic Ice Sheet plays a vital role in the overall energy balance of the earth by reflecting the majority of the sun’s energy out of the atmosphere, helping to keep the planet cool.

Storing

The Antarctic Ice Sheet contains around 70% of the freshwater on the planet. By storing it as ice, it helps to keep sea levels stable.

Read more

Storing

The Antarctic Ice Sheet contains around 70% of the freshwater on the planet. By storing it as ice, it helps to keep sea levels stable.

The Antarctic Ice Sheet contains enough to bury the United States and Mexico under more than a mile (2 kilometers) of ice.

By locking up all this water, the ice sheet plays an important role in setting sea levels around the planet. For over 10,000 years, sea levels have been relatively stable. However, they have changed many times over millions of years. During a warm period around 400,000 years ago, sea levels rose by over 20 feet (6 meters) due to melting Antarctic ice.

For tens of thousands of years the ice sheet has been large, keeping sea levels relatively low.

Regulating

Antarctic ice, in combination with the cold, dry atmosphere above it and the Southern Ocean that surrounds it, acts as a powerful global thermostat.

Read more

Regulating

Antarctic ice, in combination with the cold, dry atmosphere above it and the Southern Ocean that surrounds it, acts as a powerful global thermostat.

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is changing

Antarctic Ice

Ice is melting more quickly than new snow can replace it, and the rate of loss is increasing.

Each year, the ice sheet is shrinking more rapidly.

ANTARCTIC ICE

Land Ice: Ice shelves

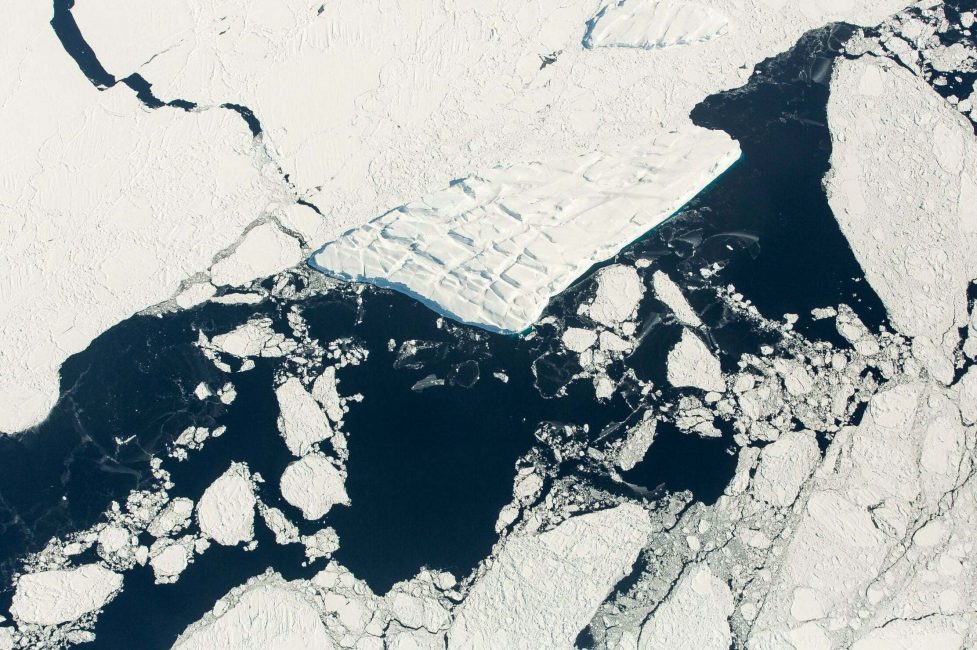

When the ice sheet reaches the sea it keeps flowing over the ocean as a floating plate of ice called an ice shelf.

Ice Shelves

Antarctic Ice

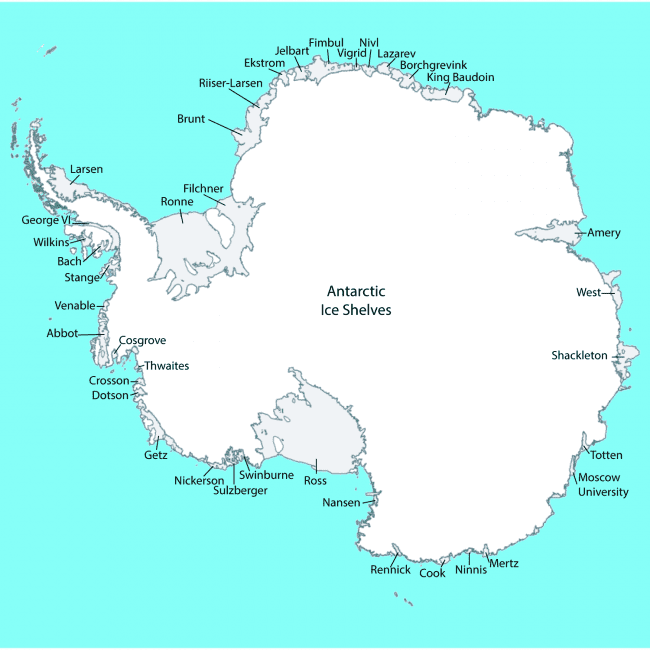

There are approximately 300 ice shelves around Antarctica. Together they cover around three quarters of the Antarctic coastline – roughly the same area as the entire Greenland Ice Sheet.

Ice shelves vary in size. Some of the larger ones are the size of small nations and over a hundred feet thick. The largest ice shelf on earth, the Ross Ice Shelf, is almost as large as France. It terminates in an ice cliff more than 370 miles (600 kilometers) long, towering up to 160 feet (150 meters) above the ocean.

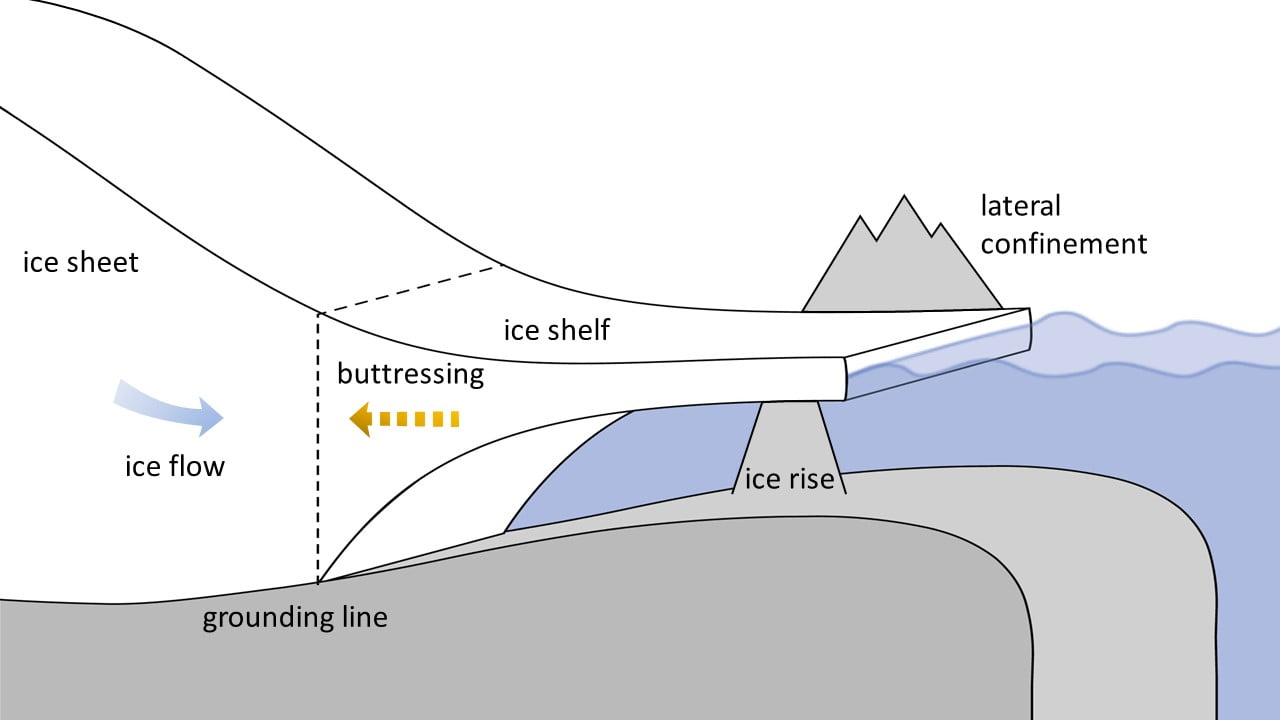

While ice shelves float on the sea, they are not considered sea ice. They are floating extensions of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, and contain freshwater ice that comes from the continent. One important difference between the ice sheet and its floating ice shelves is that ice shelves don’t contribute to sea level rise when they melt. As they are floating, they have already displaced the same amount of water they contain – much like when you put an ice cube in a glass, and the water level goes up. However, ice shelves play an important role in slowing sea level rise by slowing the flow of the ice sheet itself.

Why are ice shelves important?

Ice shelves support Antarctic ecosystems and play a vital role in slowing global sea level rise.

Stabilizing

Ice shelves act as a brake for the Antarctic Ice Sheet. When they collapse, the ice sheet begins to flow more quickly, leading to sea level rise.

Collapsing ice shelves don’t contribute directly to rising sea levels because they are already floating on the ocean, but they do offer a critical line of defense. Ice shelves act as a brake for the glaciers that make up the Antarctic Ice Sheet. When ice shelves melt the glaciers behind them soon follow, contributing directly to sea level rise.

Ice shelves slow the flow of the ice sheet by pushing back against the glaciers that feed them, helping to slow their flow by acting as a buttress, or a braking system for the ice. As ice shelves flow out over bays and inlets they may run into obstacles, such as peninsulas, islands or ice rises. These ’pinning points’ obstruct the flow of the ice shelf and slow it down.

As the ice shelf continues to push against these features, pressure builds up. This pressure is transferred back against the ice sheet, restricting its flow. When ice shelves break apart, this backward pressure is released and glaciers can flow unrestrained into the sea.

Ecosystems

Beneath the ice shelves is a unique habitat where unusual and highly specialized fish, crustaceans and invertebrates thrive.

For many years researchers thought life couldn’t survive under ice shelves with no light and no obvious food source. In recent years, new advanced drilling technologies have granted researchers access to these remote, inaccessible habitats for the first time. Drilling into the ice shelf over 5 miles (8km) from open water, they are returning with reports of diverse, complex ecosystems – and evidence they have survived under the ice for thousands of years.

Beneath the Ross Ice Shelf under nearly 2,500 feet (740 meters) of ice, communities of fish, jellyfish and amphipods (a kind of crustacean) thrive in extremely cold, dark waters. An array of life including brittle stars, soft corals and anemones has also been found under the McMurdo Ice Shelf, 50 miles (80km) from open water and the natural light and fresh nutrients it may provide.

New research is continuing to redefine what can survive in these extremes. Until very recently, scientists believed that stationary filter feeders, such as sponges, could not exist under ice shelves due to their inability to travel in search of scarce food sources. However, in February 2021 researchers reported finding a community of immobile marine organisms, including sponges, stuck to a boulder beneath the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, an incredible 160 miles (260km) from open water.

These remarkable ecosystems hold many secrets yet to be discovered, and researchers are continuing to discover new life under the ice.

Melting Ice Shelves

Antarctic Ice

Every year for the past 25 years, Antarctic ice shelves have been losing mass.

Many are becoming thinner, smaller and more vulnerable to sudden collapse on a vast scale.

This has resulted in the loss of massive ice shelves over the past several decades.

ANTARCTIC ICE

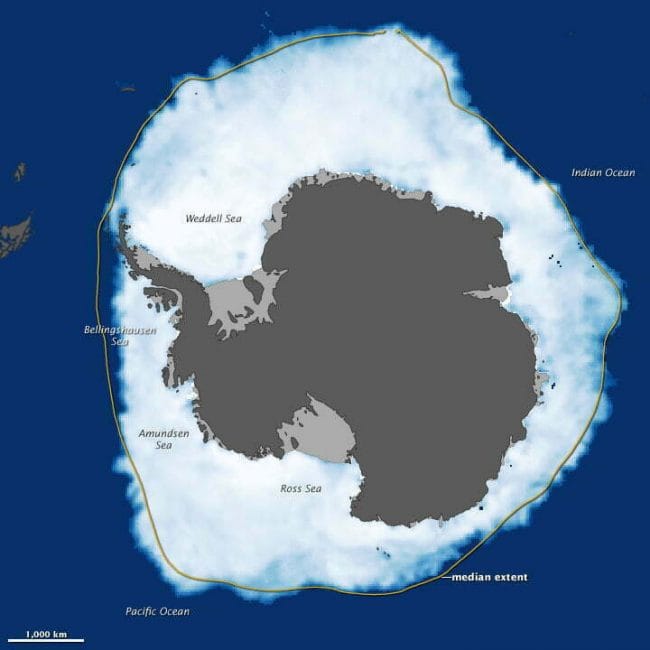

Sea Ice

Each winter, the Antarctic coastline is transformed as the ocean freezes over, surrounding the continent with a fringe of ice.

At its winter maximum, Antarctic sea ice covers an area of around 11 million square miles (18 million sq.km): almost twice the size of the United States of America, and larger than Antarctica itself.

How does sea ice form?

Antarctic Ice

Unlike the Antarctic Ice Sheet and ice shelves, which formed over millennia, Antarctic sea ice forms over weeks, days or even hours. When sea temperatures drop below 28.4°F (-1.8°C)* sea water begins to freeze. Small crystals begin to form in the ocean, which gradually accumulate into slush, then ice.

Exactly how the sea ice forms depends on the state of the sea. In a quiet, sheltered bay, sea ice may form as a surface slick, gradually becoming thicker and deeper. In stormy seas, ice crystals may form in both shallow and deep water, colliding and congealing into plates of sea ice over time.

Why is sea ice important?

Antarctic sea ice has impacts on a global scale.

Keeping the planet cool

The white surface of the sea ice reflects much of the sun’s heat back to space, helping to keep the Earth cool.

Protecting Antarctic ecosystems

Sea ice is an important habitat for phytoplankton, microscopic plants which form the foundation of the Antarctic food web.

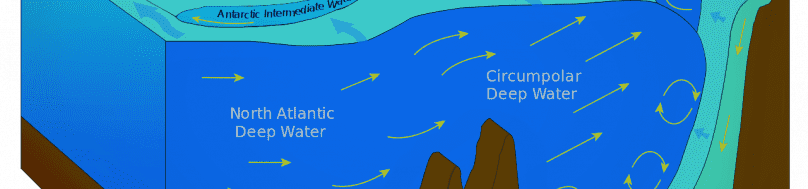

Supporting global ocean circulation

When sea ice forms it creates Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), the heaviest, most dense water on the planet.

Essential habitat for emperor penguins

Emperor penguins breed, incubate their eggs and raise their young on the sea ice. They need a solid, stable platform of sea ice for around 9 months each year, to allow their chicks to mature and become independent before the sea ice breaks apart.

Changing sea ice

Antarctic Ice

Antarctic sea ice is changing dramatically as the climate crisis continues to advance. Sea ice around Antarctica has become increasingly volatile, with record breaking lows reached twice between 2017 and 2022. In February 2023 the Bellingshausen Sea west of the Antarctic Peninsula was ice free for the first time in the satellite record.

More research is needed to understand the complex factors contributing to the rapid decline of Antarctic sea ice. However, its decline is an urgent reminder of the need to take action to reduce the impacts of the climate crisis.

ANTARCTIC ICE

Help keep Antarctic ice frozen

The climate crisis threatens to destabilize the very systems that humans need for a stable, livable world. Keeping Antarctic ice frozen is important for us all.

Join ASOC as we work at the highest levels of Antarctic governance to push for sensible, science-based policies to keep Antarctica cold.

KEEP LEARNING

Related reading

Photo credit: Erwan AMICE (Diplulmaris antarctica)

Scientific consultation: Tas Van Ommen, Antarctic climate scientist specializing in ice core palaeoclimate and glaciology.

Now that you’ve learned about Antarctic ice, read on to learn more about this extraordinary continent.

ASOC

ASOC