A dynamic habitat

CHANGING LIFE

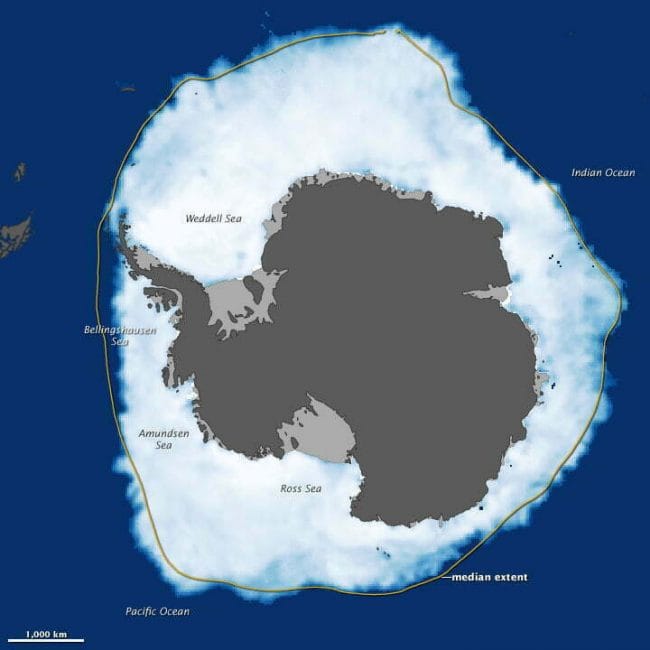

Each winter, an area of the Southern Ocean roughly the size of the United States freezes around the Antarctic coastline.

This sea ice provides a protective layer over the ocean: a cover that insulates it against the strong winds and cold temperatures above, and creates a sheltered habitat for life to flourish.

Sea ice ecosystems

CHANGING LIFE

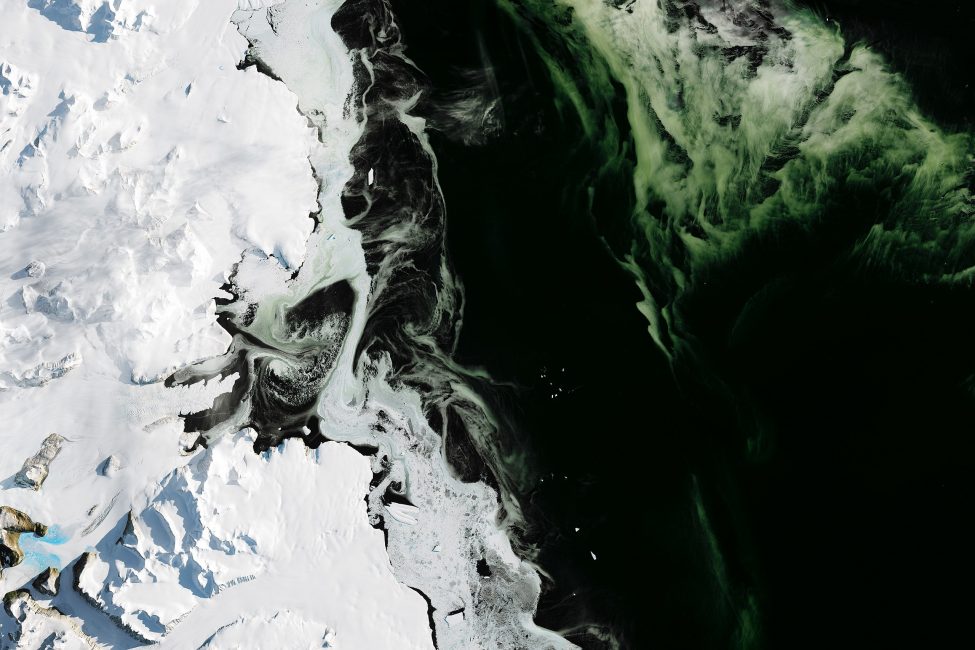

Sea ice ecosystems begin with single-celled species, including bacteria, protozoa and microscopic phytoplankton (sea plants) such as algae. They grow on the underside of the sea ice, which acts as a substrate – the equivalent of soil in the lower latitudes.

Miniature ‘forests’ of microscopic organisms create a banquet for tiny animals – zooplankton such as copepods and Antarctic krill – which graze on the underside of the ice.

These tiny animals form the basis of the food web, providing nutrients and energy to seals, penguins, whales and other marine creatures.

Emperor penguin rookeries

CHANGING LIFE

While the underside of the sea ice is an important habitat for Antarctic algae, krill and other small plants and animals, the sea ice surface is an important habitat for the largest penguins on the planet: emperor penguins.

Emperor penguins breed, incubate their eggs and raise their young on the sea ice. They need a solid, stable platform of sea ice for around 9 months each year, to allow their chicks to mature and become independent before the sea ice breaks apart.

Sea ice around Antarctica is declining, with serious impacts on emperor penguin colonies.

Penguin colonies on unstable ground

CHANGING LIFE

Emperor penguins are highly sensitive to changes in sea ice.

If sea ice forms too late, or there is too little, emperor penguins do not have enough space to breed, raise chicks, hide from predators and rest while molting (replacing their damaged feathers).

If there is too much sea ice, the distance between their colony and their open water feeding grounds becomes too large. This longer journey can lead to exhaustion and starvation for emperor penguins and their chicks.

Even when the amount of sea ice is just right, if it breaks up before the chicks are fledged and independent, entire generations can be lost.

Catastrophic breeding failures

CHANGING LIFE

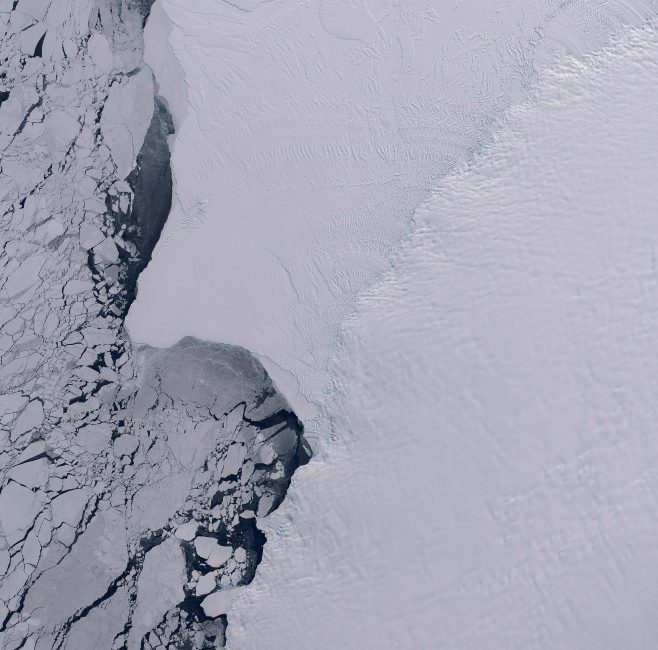

Halley Bay in the Weddell Sea used to be the site of the second-largest emperor penguin colony in Antarctica. Between 2015 and 2018, almost no chicks survived the breeding season.

Very high resolution satellite images showed that sea ice cover in Halley Bay reached record lows between 2015 and 2019. It formed later, covered less area and broke up earlier than in previous years.

Penguins abandon colony

CHANGING LIFE

Since then, sea ice cover has continued to decline.

In the summer of 2022 sea ice in Antarctica’s Bellingshausen Sea plunged to historic lows. Some areas were completely ice-free for the first time in the satellite record.

In the spring, emperor penguin colonies in the surrounding area suffered widespread breeding failure when the sea ice broke up before the chicks had fledged.

Entire ecosystems at risk

CHANGING LIFE

Penguins are an indicator species: the health and size of their population reflects the overall health of their ecosystem.

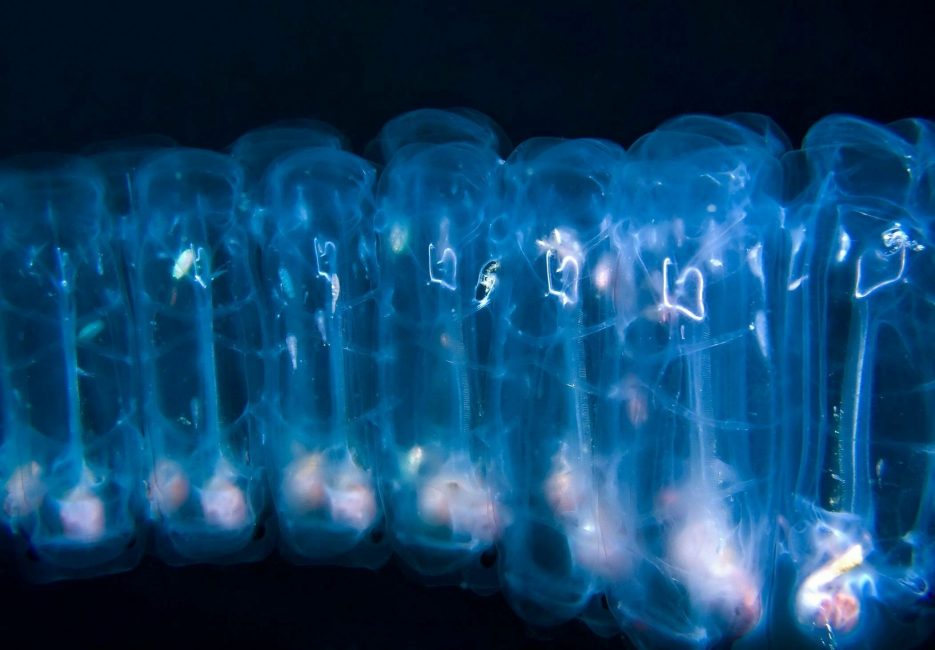

Research has shown that some phytoplankton communities are changing in areas with less sea ice. Salps are becoming more common, and Antarctic krill are shifting poleward in search of cooler waters and winter sea ice.

CHANGING LIFE

What ASOC is doing

With the support of our members, partners and a global network of Antarctic advocates, we work at the highest levels of Antarctic governance to push for the strongest possible protection for Antarctic ecosystems.

KEEP LEARNING

Related reading

Scientific consultation: Heather Lynch, Professor of Ecology and Evolution, School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University.

Now that you’ve learned how changing sea ice is affecting life in Antarctica, read on to learn more about extraordinary Antarctica.

ASOC

ASOC